Dear beloved readers,

Wishing you all a very bonne année! With a new job, and a sister who is making an unbelievable recovery, the bad vibes of 2019 are getting shaken off tout suite, replaced by exciting new ideas and adventures.

Speaking of shaking off bad vibes - whew, that Coco Chanel, amiright? I’ve always wanted to tell her story, and I’ve struggled to do so the right way: how to convey both how incredibly influential she was and give respect to the way she changed the craft of fashion for good, without glossing over the fact that she was an actual Nazi-lover? I first began working on that episode back in November, and that is just too much time to spend inside the mind of an anti-Semite. So for this first newsletter of 2020, I’d like to shine a spotlight on a lovely foil to Coco Chanel: someone who struck another, braver path when the Germans came calling. Let’s talk about Catherine Dior.

The original Miss Dior

A young Catherine Dior, in happier times

Catherine Dior, her older brother Christian, and their two other siblings all grew up on the coast of Normandy. At first, Catherine was raised in considerable wealth, thanks to her father’s successful fertilizer business, but the 1930s brought nothing but grief to the Dior family. Catherine’s mother died, her brother Bernard suffered a nervous collapse, and her father’s business suffered a financial collapse. Catherine and her father moved out to the countryside, living simply and cheaply. They relied on contributions from Christian Dior, now a young man apprenticing at a couture house in Paris. But this meager stream of income was about to be disrupted. At the outbreak of World War II, Christian enlisted in the army, and Catherine turned her new family home into a working farm.

Provincial as their new rural home might have been, Catherine had worked hard to transform it into a beautiful oasis of tranquility. Inheriting her late mother’s green thumb, Catherine filled the grounds with lush, delicate roses and heady jasmine. With the arrival of war, Catherine promptly pulled up her beloved roses in favor of green beans and peas. When France surrendered to the German blitzkrieg, Christian Dior found himself making his way through the Exodus to Catherine, where he rolled up his sleeves and channeled his energy into the harvest.

By 1941, life was returning to a strange sort of normal in Paris. Coco Chanel may have closed her fashion house, but the others couldn’t afford such a luxury. Christian Dior was offered a position by his old employer: return to the couture houses, design gowns for rich women, make money for your family. The problem was, those rich women were no longer aristocratic French socialites - they were Nazi officers’ wives and mistresses. Nevertheless, Christian dusted off the dirt, returned to the workshop, and duly spent the war sewing those wives and mistresses into exquisite couture. His is a more nuanced tale of collaboration - remember, Chanel was one of the richest women in the world when she offered her services to the Nazis, while Christian was a poor young man with four siblings and an elderly father to support - but it’s hardly a point of pride for the House of Dior.

Back home, however, Catherine was walking a different path. In 1941, just as Christian returned to the couture houses, Catherine fell in love. Hervé Papillault de Charbonneries was older, married, a father of three…and an active member of the fledgling French Resistance. With an introduction from Hervé, Catherine quickly joined the fight against the Nazis. Catherine exploited her youth and beauty to acquire enemy intelligence: young Nazi officers were happy to let a lovely girl ride around the countryside on her bicycle, never suspecting that she was making a mental record of their troop movements. They were happy to let the pretty young thing take their photos, never realizing that the moment their backs were turned, Catherine focused her camera on their Top Secret documents. For three years, while Coco dined with Nazi officers and Christian sewed their girlfriends into new gowns, Catherine funneled her reports and photographs to British intelligence officers. When she passed through Paris, Catherine stayed at her brother’s apartment on the Rue Royale. Christian had no idea his sister was in town - let alone that she was using his own apartment as a Resistance meeting house and a hiding spot!

But Catherine’s luck finally ran out. On July 6, 1944, Catherine was arrested and brought to the gates of Hell: 180 Rue de la Pompe, site of the Gestapo’s “kitchen” - the torture house.

180 rue de la Pompe exterior, today

Behind this typical Haussmann exterior, Gestapo agents subjected prisoners to excruciating tortures, including waterboarding, broken limbs, and the removal of fingernails with hot irons. Within these walls, Resistance heroes like Jean Moulin and Pierre Brossolette were subjected to unimaginable agonies. By the war’s end, 300 Resistance agents passed through the kitchen. Half of them were sent to concentration camps. The rest died. Astonishingly, after three full weeks in the Gestapo’s “kitchen” Catherine remained steadfast. She refused to give up a single name - not her famous brother, not her most-wanted lover, not any of the members of her Resistance network, including those she’d left behind in Christian’s apartment. When Christian returned home to chaos and realized what had taken place, he snapped into crisis mode.

He wasn’t the only one in crisis mode: on August 14, 1944, the Allied forces landed at Normandy, not too far from the Dior family’s ancestral home. The Nazis whom Coco had been charming and whom Christian had been dressing were in a state of panic. Paris fell into disarray, as the Nazis began fleeing with their lives - and anything they could steal - and as the underground Resistance networks moved into open rebellion. Amidst the collapsing social order, one last train pulled out of the Pantin train station, carrying 600 women to Ravensbrück concentration camp outside Berlin. One of those women? Catherine Dior. In a way, she was lucky: back at 180 rue de la Pompe, the Gestapo were summarily executing all of their prisoners in advance of the Allied army’s arrival in Paris. The train inched its way to the German border, braking for German troop trains, braking for German loot trains, braking to avoid Allied air strikes, speeding away from Resistance members trying to sabotage the tracks and Red Cross officers pleading for mercy. As the train crawled only 60 miles in two days, the trains overheated, and prisoners began dying in the railway cars. It was a race against the clock: Christian received an assurance from the Swedish Consul that if Catherine’s train was still on French soil on August 17th, the Germans were willing to hand Catherine over to the Swedes. “It’s a matter of timing,” Christian explained to a friend. “If her train has not passed Bar-le-Duc by 2:45 this afternoon, she will be handed over. Otherwise, it will be too late and there will be nothing we can do…” Yet despite the delays, Christian’s contacts were too late: Catherine’s train slipped into Germany and before long, she was inducted into Ravensbrück: head shaved, tattooed 57183RA, wearing the red triangle insignia of a Resistance fighter.

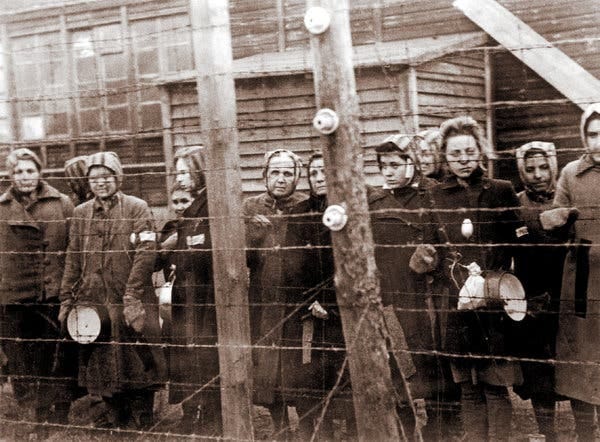

Prisoners at Ravensbrück camp

Over the course of the next year, Catherine was overworked, underfed, and shuffled across Germany’s network of concentration camps stretching across the Reich. Together, Catherine and her fellow prisoners suffered malnutrition, tuberculosis, typhoid and dysentery. At each step in her journey, Catherine was forced to manufacture instruments of war for her captors: explosives in Torgau, potash in Abterode, machinery in Prussia, and finally, airplane parts in Leipzig. On April 13th, the Leipzig camp ordered the prisoners on a “Death March”: without food or water, the prisoners were forced down the road and shot on site if they tried to escape. Somehow, Catherine slipped away into the woods, and emerged on the brink of death in the bombed-out rubble of Dresden. Discovered by American soldiers, the emaciated Catherine spent the next month in a hospital - all while her brother searched for her frantically. On May 17th, 1945, Christian Dior received the phone call he’d been hoping for: the next morning, Catherine would arrive in Paris the way she’d left, stuffed into an overcrowded train.

Refugees and concentration camp survivors reunite in Paris after the war

On the platform of the Gare de l’Est, Catherine and Christian Dior reunited at last. Catherine looked ghastly: starved, broken, desperately ill, practically unrecognizable. When the siblings returned to Christian’s apartment at 10 Rue Royale - where Catherine had been staying the night before her arrest - Christian wanted to celebrate. He prepared Catherine’s favorite dish, a cheese soufflé. It would be months before Catherine could stomach real food again.

Catherine Dior, wearing her Resistance medals

Like so many female survivors of the concentration camps, Catherine struggled to forge a new place in a society which did not want to hear her story. She testified against her torturers in the Rue de la Pompe, but otherwise rarely spoke about her wartime experiences. Catherine received the Croix de Guerre and the Croix du Combatant Volontaire de la Résistance from France, the Cross of Valour from Poland, and the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom from Britain. Most treasured, however, was a gold bracelet from the Franco-Polish Resistance network, etched with the dates of her capture and liberation. She wore it every day.

Following the war, Catherine moved into Christian’s apartment, along with her now widowed lover in the Resistance, Hervé and his children. Hervé and Catherine would spend the rest of their lives together - but what kind of life would it be?

What I remember most about the women who were part of my childhood was their perfume; perfume lasts much longer than the moment.

- Christian Dior

On February 12, 1947, Christian Dior unveiled his first couture collection, with Catherine sitting quietly in the audience. Dubbed the “New Look” by the press, the collection was a turning moment in the history of 20th century fashion. Christian’s designs made him an overnight success, and Dior would pick up the mantel abandoned by Coco Chanel as the premier fashion designer of France. (Needless to say, Chanel hated him.) Christian’s couture line wasn’t the only thing launched that day, however. That afternoon, Christian launched his first perfume: a heady scent of roses, a perfume, Christian said, “that smells of love.” Christian named the creation Miss Dior in tribute to his brave, beloved sister. The perfume would set the course of the rest of Catherine’s life.

Catherine and Christian linger among their beloved flowers

Shortly after the war, Catherine returned to her father’s house, where she had once planted roses and then planted peas. In 1951, Christian used the oodles of money he’d accumulated through sales of couture and Miss Dior to purchase a chateau in Grasse, only three miles down the road. Catherine, the green thumb of the family, returned at last to her beloved roses and jasmine, this time managing the gardens of her father’s house as well as those of her brother’s. Catherine became an expert in the production of those most essential florals: centifolia roses, lily-of-the-valley, lavender. She sold her flowers to the House of Dior, to the perfume houses of Grasse, and to flower houses around the world. In fact, Catherine became one of the first women in French history to acquire a license to sell flowers, and each week she and Hervé would return to Paris to sell her bouquets at Les Halles marketplace. Before heading back to the countryside, Catherine would stop by Christian’s atelier with bunches of his favorite flower, lily-of-the-valley, which he would sew into the hems of his gowns.

In 1952, Christian Dior died unexpectedly of a heart attack at the impossibly young age of 52. Left in charge of her brother’s funeral, Catherine arranged an enormous mountain of flowers to be placed in front of the Arc de Triomphe:

As the official historian of Dior recalls, “A local essential-oil producer told me how she would arrive with her harvest and declare the weight of the flowers. He said that he always paid the price without weighing them again, because it was well known that Catherine was utterly trustworthy.” In her farmhouse, surrounded by Christian’s Chagall paintings and antique furniture, Catherine continued gardening roses and jasmine well into her 70s. Catherine passed away in 2008, at the age of 91, having spent the last fifty years of her life among her flowers. In 2013, Christian’s chateau was purchased by Parfums Christian Dior and underwent a restoration. In 2016, the restored chateau reopened, with Catherine’s beautiful gardens still blooming, the centifolia roses and lilies of the valley drifting into the warm Provençal air.

In 1949, following the success of his couture line and perfume, Christian Dior merged the two creations into his iconic “Miss Dior gown” - a miniature dress woven out of real roses, jasmine blossoms, and lilies of the valley.

Until now, there’s never been a proper recounting of Catherine Dior’s life, which is why I am thrilled to hear about Justine Picardie’s upcoming biography Miss Dior, scheduled for release in Autumn 2020. I’ll let all of you know when it’s available for pre-order!

Here’s a lovely video showing a re-construction of the Miss Dior dress:

Finally, meet the new Catherine Dior: Armelle Janody, the Grasse florist providing flowers to the House of Dior today:

Thank you all for this longwinded journey through Catherine Dior’s life - I simply love her, and I hope that now all of you do, as well. Keep her story in mind during next month’s episode, which will focus on the lives of female Résistantes like Catherine. Until then, thanks again for reading and listening, and until next time, au revoir!

Bisous,

Diana